By Lisa Desai and Yasmeen Qureshi

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

Bethany Quinn and her husband Sean moved into their home in Stuart, in Martin County, three years ago.

About This StoryThe Florida Center for Investigative Reporting partnered with journalists Lisa Desai and Yasmeen Qureshi and PBS NewsHour Weekend for this story. Media PartnersFlorida Courier The Ledger PBS NewsHour Weekend Sun Sentinel |

As a girl, Bethany Quinn swam in the St. Lucie River. Now she won’t let her two daughters near the water. (Photo by Daniel Traub.)

It’s the same house Bethany grew up in, nestled in a middle-class neighborhood and across the street from the St. Lucie Lucie River, part of the larger Indian River Lagoon estuary.

As a girl, Quinn would swim in the river with her family. But today Quinn doesn’t allow her two daughters to go near the water. The river isn’t safe, in her view; it’s too polluted.

“I just don’t see how it can come back,” Quinn said.

The Indian River Lagoon, stretching 156 miles along Florida’s Atlantic coast from Ponce de Leon Inlet in New Smyrna Beach to Jupiter Inlet north of West Palm Beach, is one of the most biodiverse waterways in North America. The estuary is home to thousands of species of plants and animals, including more than 800 dolphins.

It also represents a significant part of the Florida economy. With an economic value of $3.7 billion, the Indian River Lagoon supports 15,000 jobs and is responsible for $1.3 billion in annual recreational spending, according to the St. Johns River Water Management District.

But the Indian River Lagoon faces a grave environmental emergency, according to reporting by PBS NewsHour Weekend in partnership with the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting. Cleaning up the estuary will take decades and hundreds of millions of dollars in a process that will directly affect everyone who lives near the waterway.

Algae on the surface of the water in the Indian River Lagoon. (Photo by Daniel Traub.)

Contamination of the lagoon from fertilizers and nearby septic tanks has steadily increased every year for more than a decade, with state environmental and health officials largely ignoring the problem and continuing to issue permits for new septic tanks. This year marked a tipping point for the contamination.

All over the Indian River Lagoon, there is evidence today of algal blooms, and in some parts of the waterway, the algae is in the form of toxic blue-green scum. These algal blooms starve plant life and can destroy the marine ecosystem.

In March 2016, the contamination in the lagoon led to one of the biggest fish kills in the estuary’s history. At its worst, thousands of dead fish could BE seen floating lifeless on the lagoon’s surface.

Dolphins in the lagoon have tested positive for E. Coli and antibiotic-resistant bacteria likely as a result of untreated sewage leaching into the water, which could cause many of the dolphins to be sickened and die.

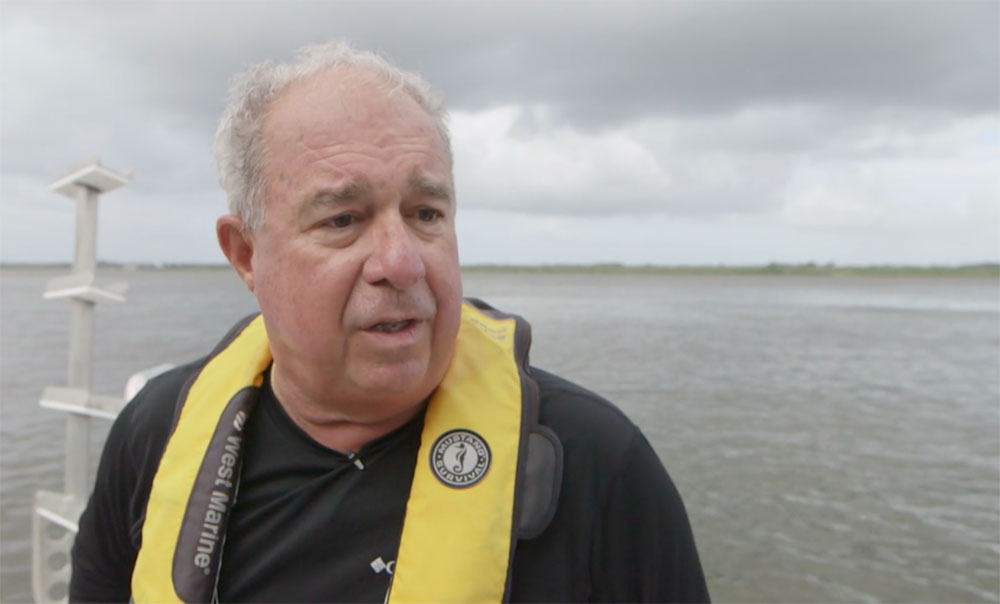

“We’re having a crisis in the Indian River Lagoon from excessive amounts of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus that are causing harmful algae blooms,” said Brian Lapointe, a scientist at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. “Some of these are toxic and some are not toxic, but still cause ecological damage.”

Brian Lapointe, a scientist at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, has been studying the contamination of Indian River Lagoon. (Photo by Daniel Traub.)

Man-made problem

The Indian River Lagoon’s crisis is man-made.

Since the 1960s, the population of the five counties around the lagoon has doubled. Many of the 600,000 houses that surround Indian River Lagoon use septic tanks instead of a county or municipal sewage systems.

“The problem is septic tanks really don’t treat the sewage to a very high level,” Lapointe said. “They are not engineered to remove nutrients, and they don’t disinfect.”

Septic tanks don’t treat sewage. Instead, they rely on dense soil to filter out contaminants. But septic tanks don’t perform well in the porous soil of Florida’s coastal areas. The septic tanks are leaching into tidal creeks and canals that flow into the Indian River Lagoon.

The sensitive estuary also receives high levels of fertilizer run-off and takes in discharge from Lake Okeechobee. When untreated sewage from septic tanks combines with these other pollutants, algal blooms result, creating an overgrowth of algae that can be seen as colorful scum on the water’s surface.

“We have two major problems — that discharge from the lake bringing a lot of fresh water into the system and then all the septic tanks that are also draining into the system with fecal coliform bacteria … and it really is like the perfect storm coming together creating a big, big problem in this area,” said FAU’s Lapointe.

Don’t go in the water

Bethany and Sean Quinn live across from the St. Lucie River, which they believe is too polluted to use. (Photo by Daniel Traub.)

Bethany and Sean Quinn know their house in Stuart is part of the problem. Buried in their front yard is a septic tank, one of 30,000 in Martin County alone.

“If I had my preference, I’d much rather have it be something that goes and is treated and the water’s reclaimed and turned into something useful,” Sean Quinn said.

In May, the St. Lucie River became so polluted that state health officials warned residents not to even touch the water.

“I know people aren’t catching as much fish. You don’t see any of the seagrass. You rarely see shells,” Quinn said. “It’s changing right before our eyes.”

Despite the visible problems, many Floridians are largely unaware of the adverse effects of septic tanks because state officials continue to permit their installation near Indian River Lagoon.

According to the Florida Department of Health’s website, more than 100 new septic tank permits were issued in July in the five-county region around the lagoon. State health officials declined to comment about the state’s continued permitting of septic tank installations around the estuary.

An expensive solution

Martin County Commissioner Doug Smith is spearheading a 20-year, $138 million project to clean up the river by connecting more than 10,000 houses that rely on septic tanks to sewage lines.

Martin County Commissioner Doug Smith is spearheading a project connect more than 10,000 homes to sewage lines. (Photo by Daniel Traub.)

Homeowners in Martin County will be required to replace septic tanks and connect to sewage lines, at a cost of about $8,500 per homeowner. Under the project, those who cannot afford septic tank removal can pay in installments over 20 years through their property tax bills.

“People want to have good, healthy water. They want it to be clean water, and it really should be,” Smith said. “Generations ago it was … and so everybody’s hope is that we can get back to that.”

Last month, Gov. Rick Scott described septic tanks as a “major contributor to the pollution in these water bodies.” He also said he would propose new funding for a 50 percent matching grant to help curb pollution in the Indian River Lagoon and assist homeowners moving from septic tanks to sewer lines.

Among homeowners who have signed up to remove their septic tanks is Suzie Debartolo. Her house in Martin County overlooks the St. Lucie River. She used to enjoy being on the water, but she’s since sold her boat and stored away her kayaks.

“You see how that is just totally dead?” she said, pointing to the river. “You don’t see any sign of life down there … I wouldn’t dare get in here.”

The Florida Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit news organization supported by foundations and individual contributions. For more information, visit fcir.org.