By Susannah Nesmith

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

Daddy A+Plus was living in a five-bedroom house with a pool in suburban Miami-Dade County in 2009.

About This StoryThis story is the result of a collaboration between FCIR and WFOR/CBS Miami. Media PartnersEn Español |

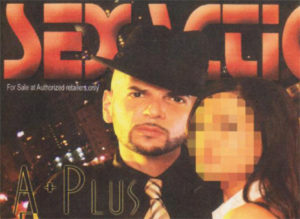

Daddy A+Plus, whose real name is Alexander Valdes, was on the cover of a South Florida adult entertainment guide.

He had drugs and easy money. He also had girls, lots of girls.

Daddy A+Plus was a pimp, and business was thriving. He even appeared on the cover of the adult entertainment guide Sex Action, which proclaimed that he was “taking over the game.”

His success was not uncommon. Around the country, pimps like him force thousands of people, mostly women and girls, into prostitution every day. Florida has the third highest number of sex trafficking cases reported to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center.

Today, Daddy A+Plus, whose real name is Alexander Valdes, is inmate number M08160 at South Bay Correctional Facility in southwestern Palm Beach County. His presence behind bars represents a success in Florida’s battle against sex trafficking.

One of relatively few successes.

For more than 15 years, a coalition of victim advocates, sociologists and prosecutors has waged a nationwide campaign to change the way the criminal justice system handles prostitution. Reformers have argued that prostitutes are victims, not criminals, and more effort should be made to go after human traffickers – the pimps. Instead of incarceration, services such as counseling should be made available to the victims, these advocates say.

Florida revised its laws in 2012 and 2013 to increase the penalties for sex trafficking, funnel additional resources into treatment for child victims, and make it easier to convict traffickers of juveniles. Last year, state legislators approved the creation of the Statewide Council on Human Trafficking, chaired by State Attorney General Pam Bondi. This year, the legislature approved funding for the first shelter for adult trafficking victims, which is located in Miami-Dade County.

“It is the intent of the Legislature that the perpetrators of human trafficking be penalized for their illegal conduct and that the victims of trafficking be protected and assisted by this state and its agencies,” a statute passed in 2012 stated.

Despite this new focus, a statewide analysis by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting, in collaboration with WFOR/CBS Miami, found that efforts in the state to investigate and prosecute sex traffickers have yielded few results.

By mid-October, only 24 men and women were in Florida prisons convicted of sex trafficking. Meanwhile, hundreds of prostitutes are still being arrested annually. Last year alone, police filed nearly two dozen cases against child prostitutes, according to the Department of Juvenile Justice.

“Law enforcement is not necessarily on the same page,” said Elizabeth Fisher, a Sarasota advocate who runs Selah Freedom, an organization that helps victims of sex trafficking and conducts workshops at police departments. “They’re just learning. Literally just a year and a half ago, law enforcement was saying this isn’t happening here. Undoing that myth about prostitution is hard and takes time.”

Prosecutions rare

Victim advocates say the image of the independent prostitute, working for herself and selling sex by choice, is rarely accurate. Many adult prostitutes first got involved in the sex trade as children.

“I think the majority who are in the life have been the victims of trafficking,” said Katariina Rosenblatt, founder of There Is HOPE for Me, a volunteer organization that raises awareness about sex trafficking in South Florida. When “they’re arresting prostitutes, they’re arresting victims,” she added.

“We’ve never met somebody in the life who was working by themselves and not working for a trafficker,” said Sarasota’s Fisher. “We’ve worked with hundreds of victims over the last couple years.”

But few of their traffickers are going to prison.

Attorney General Bondi has vowed to make Florida a “zero-tolerance state for human trafficking.” At a recent meeting of her human trafficking council, a Department of Children and Families official said the department serves 200 juvenile victims of human trafficking “on any given day.” Yet Bondi’s office identified only 51 defendants her prosecutors had charged with trafficking-related offenses since she was elected in 2010. Half of those were charged in a single recent case.

“In 2012, I fought for legislation to make it easier for all Florida prosecutors to pursue human trafficking cases and since then, we have seen an increase in the number of human trafficking investigations throughout the state,” Bondi said in a statement. “Thanks to these efforts and the great work of law enforcement officers and advocates, countless victims have been saved.”

She has called human traffickers “monsters” who “belong behind bars.” Of the 14 defendants convicted, three received probation and eight received less than five years behind bars. Only one of the 14 got more than 10 years in prison.

So far, only one jurisdiction in the state has mounted any concerted effort to tackle the problem.

Plan of attack

Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle started a dedicated Human Trafficking Unit three years ago, helped establish a think tank at the University of Miami to study the problem, and initiated a public relations campaign, using flyers, billboards and bus bench ads to advertise help available to victims.

An Urban Institute study estimated that sex trafficking was a $235 million industry in Greater Miami in 2007.

Last year, Fernandez Rundle’s office added two victims’ specialists to the Human Trafficking Unit. They have already worked with more than 100 victims. Even if a criminal case against the trafficker is dropped, the counselors will continue to help the victim.

“The hardest thing really has been hanging on to the victims,” Fernandez Rundle said. “Trying to encourage them to break away from that bond that they’ve had with this predator.”

Of the 24 prisoners convicted of sex trafficking in Florida prisons, 15 are from Miami-Dade County. Seven of the prisoners are from Orange County, which encompasses Orlando. The final two came from Pinellas County, where St. Petersburg is located, and Collier County, which includes Naples.

In context, Miami-Dade’s successes can seem small.

From 2010 through 2014, Miami-Dade police agencies and prosecutors charged 250 defendants identified by Fernandez Rundle’s office as involved in sex trafficking. Only 36 of those defendants went to prison on any charge by early 2015. Meanwhile, prosecutors had dropped the charges against one-third of the defendants whose cases were resolved. Of the 250 defendants, 85 were accused of victimizing children.

Those numbers contrast starkly with the rate at which prostitutes are arrested – an indication that the attitude of police departments has generally failed to evolve with the new mandate to target traffickers.

Police in Miami-Dade County filed more than 3,200 prostitution cases against men and women and 37 cases against children during the same five-year time period (multiple cases can be filed against one defendant). The cases against children are not public record, but Fernandez Rundle said all but a few were dropped. Records show prosecutors won convictions in more than 1,000 of the adult prostitution cases.

Investigative challenges

City of Miami Police Commander Jose Alfonso stops a suspected prostitute along SW 8th Street in Miami to check for outstanding warrants and offer an opportunity to say if she is being coerced or abused. Until recently, Alfonso was assigned to Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle’s human trafficking unit. (Photo by John Van Beekum/FCIR.)

For the majority of police, arresting prostitutes is often easier than investigating pimps.

“Everybody’s learning how to handle this right now,” said Miami Police Commander Jose Alfonso, who until recently was assigned to Fernandez Rundle’s Human Trafficking Unit, which is housed in a windowless office at the state attorney’s office. “It’s a difficult crime to investigate. It’s a difficult crime to prosecute. It’s always been out there. We just gave it a name. I think in a lot of jurisdictions, it’s still looked as if the girls are willing participants.”

The prostitutes themselves can make cases hard to investigate.

Alfonso kept a picture tacked to his bulletin board of a snarling kitten with claws out, his way of thinking of the women and girls he was trying to rescue, often in spite of themselves. He won a national award in January for his work.

“When we do stings, they’ll deny it up and down,” Alfonso said. “We know they have a pimp. We could sit there for days with them and they’ll deny it. They’re fighting tooth and nail. In their minds, we’re the enemy.”

The girls often become a defense lawyer’s best tool because they defend the pimp, or their pasts compromise their testimony.

Among his frustrations was a case involving an 11-year-old victim that had to be dropped because she told so many different stories, and another in which the victim’s heroin addiction, which started before she met her pimp, discredited her testimony.

“With some of these girls, it may take three or four interviews before a closer version of the truth comes out,” Alfonso said. “You can imagine how defense attorneys will run with that. The phone records make our cases.”

Text messages help reveal truths the victims refuse to tell. They’ve also been useful persuading traffickers to take plea agreements that save the victims from having to testify.

“Our victims are very traumatized,” Fernandez Rundle said. As a result prosecutors have to make a choice whether making a victim testify will “re-victimize her and maybe forever damage her psyche.”

In 2013, the legislature revised the human trafficking statute, removing the requirement that prosecutors prove a pimp used “force, fraud or coercion” to get a prostitute to work for him if the girl was a juvenile. According to Alfonso, the change makes it easier to pursue cases. But they’re still not easy.

“Even with juvenile victims, it gets real ugly when you get a good defense attorney who wants discovery and wants to depose the girl,” he said. “Sometimes it’s to everybody’s benefit to plead the case down.”

While very few agencies other than Miami-Dade have used the updated human trafficking statute to put pimps behind bars, Orange County prosecutors in January used it against Aaron D. George, a long-time pimp who is the only person in the state serving a life sentence for trafficking in children. George went to prison twice before for the less serious charge of living off the proceeds of prostitution.

“I think we’re armed with what we need from the legislature,” said Deborah Barra, one of the prosecutors.

Sarasota police, meanwhile, worked with the advocacy group Selah Freedom to establish a diversion program for prostitutes that includes counseling and drug treatment. Charges are dropped once a defendant completes the program.

A pimp’s life

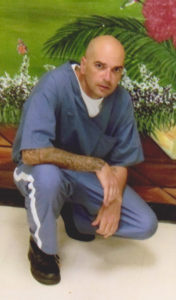

The best outcomes are in cases like the one against Valdes — Daddy A+Plus. Valdes, 40 and slim, with a shaved head and a variety of tattoos covering both forearms, spoke to FCIR and WFOR/CBS in a large, empty room at South Bay Correctional.

His criminal operation fell apart in the winter and spring of 2010. First, Miami police caught him in a prostitution sting at a hotel in the city’s Flagami neighborhood. Arresting officers said they found cocaine in his pocket. Valdes bonded out of jail within days. Three months later, a witness called 911 and reported a possible kidnapping on S.W. Eighth Street in Miami. Another witness reported seeing a man punching a woman in a car being driven erratically. That witness followed the car all the way to a suburban neighborhood where Miami-Dade police pulled it over. Valdes was driving, according to records, but his passenger told police he had not hit her and he wasn’t charged with a crime.

Finally, one of the women he had forced into prostitution contacted her father, who helped her escape.

That young woman told police that Valdes kidnapped her at a barbecue, physically forcing her into his car. After making her change clothes, he took her to a hotel where he beat her after she refused to have sex with the first stranger.

For the next 34 days, the young woman was forced to have sex with men she didn’t know as well as with Valdes, who beat her periodically and also drugged her, according to Valdes’ arrest affidavit.

After she escaped, Valdes went to a beauty school in an attempt to find her. Police arrested him after employees of the beauty school called police.

He spent the next three years fighting the charges from a Miami-Dade County jail cell. But the more Miami Dade’s Human Trafficking Unit investigated Valdes, the more crimes they found.

Valdes

Valdes, who has the word “pimping” tattooed on his right forearm, told FCIR and WFOR that he was running a legitimate escort service, not a prostitution ring. He even filed incorporation papers with the state for “A-Plus Escorts.” He was soft-spoken and polite as he tried to explain away the evidence against him.

Valdes said his definition of pimp was different from the legal or generally accepted definition. He just meant a man who paid the bills, using the money a woman made, he said.

“If a girl works in Wendy’s, and I take care of all the responsibilities and she hands me her money, am I pimping her?” he said. “She handed me all her money.”

Valdes said men paid $150 to spend 30 minutes with one of his escorts in a hotel room. But he insisted his escorts were not selling sex.

“They could do like maybe a body rub,” he said. “They could do a sexy dance. They could do the little flirt thing, you know? Keep them company, happy, you know? But nothing that breaks the law.”

He insisted the women who prosecutors say were his victims were actually drug addled and confused, but denied giving them drugs. He also denied hitting any of the women, though police took a picture of the woman who had been in the car with him. She had a black eye.

In letters investigators found and that prosecutors filed with the court, Valdes instructed a friend to stalk the women who might testify against him. His letters are specific in their directions. But Valdes said the idea to approach the victims was his friend’s.

“He tells me, ‘Hey, look, if any of those women out there, if I could help you possibly persuade them, this and that, so they won’t go to court, this and that,’” Valdes said. “And I felt at the time like everything was failing. So what else I had to do? Not even lawyers could help me.”

Prosecutors charged Valdes with 23 felonies. If convicted of all of them, he faced life in prison. He agreed to plead guilty in exchange for an 18-year prison sentence. Prosecutors were able to avoid having his victims testify against him in court.

The case against Valdes is a textbook, if rare, example of how aggressively targeting pimps can work.

Valdes claimed to be stunned by the severity of the charges against him, complaining that it was the women who got him into this trouble.

“A woman could be your rise,” he said. “But [she] could also be your downfall.”