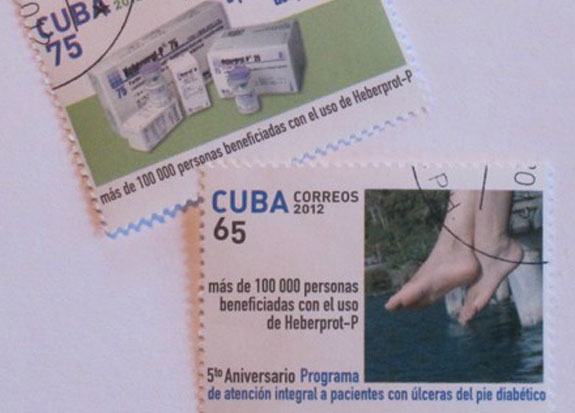

Cuban postage stamps touting the country’s efforts to save limbs of diabetics. (Photo by Andrew Schneider.)

By Andrew Schneider

FairWarning

HAVANA – President Obama’s efforts to renew relations with Cuba may soon allow Americans to visit this island’s pristine beaches and start lugging home shopping bags filled with long-coveted cigars and rum. But for frustrated American physicians battling to save the feet and legs of tens of thousands of diabetic patients, it may be a long wait before a much-heralded limb-saving Cuban drug can legally make the 90-mile trip to U.S. shores.

Because of the Cold War-spawned economic blockade against what Washington has long considered the Communist threat in the Caribbean, the developer of the medication, the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology in Havana, is forbidden to bring a nine-year-old drug, called Heberprot-P, to the U.S. for clinical trials and use.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I do know that it may be that American legs are being lost while Cuban legs are being saved because Washington agencies …won’t allow that medicine in,” said Dr. I. Kelman Cohen, professor emeritus in surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“I think all the American medical community really wants is for Heberprot to be allowed into the country for testing…Let’s get it tested and see if it will really save the thousands of limbs that many believe it can,” Cohen said.

In December, 2013, 111 members of Congress petitioned the Treasury secretary to allow the drug to be tested in the U.S., but up to now there has been no sign of progress, according to several lawmakers who signed the letter.

Diplomatic talks between Washington and the Castro government on issues such as immigration, travel and commercial ventures are scheduled to start next week. At a briefing today on Obama’s normalization plans, administration officials were asked about the status of Heberprot but were noncommittal.

A proven drug that will thwart flesh-destroying diabetic wounds is desperately sought by physicians throughout the world, according to Dr. David Armstrong, professor of surgery and director of the University of Arizona’s Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance.

Diabetes researchers at Umeå University in Sweden reported in 2013 that worldwide, a limb is lost every 20 seconds because of a foot ulcer that doesn’t heal. According to the American Diabetes Association, in the U.S. alone more than 73,000 diabetics undergo amputations every year, or about one every seven minutes.

“It just rips me apart to know that there may be something out there that has the potential to save limbs and we can’t get a chance to test it because of politics rather than public health,” Armstrong said in an interview. Each year, he and his team at the Tucson medical center spend hours in operating rooms trying to save the lower limbs of more than 11,000 patients from around the world.

“So far this year, there have been several patients who may have benefited from a study of the type needed for the Cuban drug,” he said.

U.S. surgeon David Armstrong shaking hands with patient with a severe diabetes-caused wound at one of the 60 Cuban medical facilities using the drug Heberprot-P. (Photo courtesy of FairWarning.)

Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, said that “there is politics in everything” but putting public health before politics is of prime importance to his organization, which just last month signed a agreement to work more closely with its Cuban counterparts.

“We recognize that there is opportunity for allowing them to learn from us, but even more importantly, for us to learn from them and that would include any technological advances they may have made that still need to be studied and validated,” Benjamin said.

There is nothing mysterious about the path between diabetes and the loss of a limb. Untreated or poorly treated, diabetes often interferes with blood flow to the extremities, causing vascular disease, a failure in anti-bacterial defenses and nerve damage.

Because of this loss of protective sensation, diabetic ulcers form but often go undetected. Without a proper blood supply, the tissue around the ulcer becomes infected, continues to die and the wound grows.

Hyperbaric oxygen treatment is sometimes useful, say diabetes specialists, but surgical removal of the dead flesh is the typical treatment. And at a certain point, amputation becomes the only option to save the life of the patient.

Dr. Elof Eriksson, a Harvard University professor and chief of plastic surgery and a wound care expert at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, last month returned from an international meeting of hundreds of wound specialists near Havana.

He called the results of studies presented at the conference on Heberprot’s effectiveness to treat severe diabetic ulcers “impressive.”

“The only definite answer can come from a large clinical trial,” Eriksson said.

“Hopefully, this partial release of the embargo will allow increased collaboration between Cuban and U.S. scientists and make such an investigation possible.”

The inspiration for Heberprot was developed in St. Louis years before the embargo by biochemist Stanley Cohen (No relation to Kelman Cohen), and his fellow researcher, neurophysiologist Rita Levi-Montalcini. The Brooklyn-born Cohen and his Italian-American partner received the 1986 Nobel Prize in Medicine for their discoveries of epidermal and nerve growth factors.

The Cuban research center, which released Heberprot in 2006, acknowledges the importance of work done years earlier by Stanley Cohen.

He discovered that a compound called protein recumbent epidermal growth factor stimulates cell growth.”His contribution to our work was mainly this discovery, the rest was our own research,” Dr. Manuel Raices, a scientist with the Havana research center, said in an email.

Another attendee at the December conference, Dr. Aristidis Veves, research director of the Microcirculation Lab at Boston’s Joslin-Beth Israel Deaconess Foot Center, said clinical trials have multiple benefits and will help diabetic patients not only in U.S. but throughout the world.

“Potential beneficial new treatments should be thoroughly tested regardless of the country of their origin and differences among governments,” said Veves, an international expert in non-healing wounds. “It can either bring to the market a helpful medication … or discontinue the medication that has no benefit and can only do harm.”

Regardless of what President Obama wants, the legislative reality is that the embargo cannot be ended without Congressional action. Most Cuba watchers expect the Republican-controlled Congress to move slowly at best in ending the 1996 Helms-Burton Act, also called the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act. It is the legal framework of the embargo.

Republican Marco Rubio, Florida’s junior senator and a Cuban-American, instantly reacted to the White House announcement on improving relations between the two Cold War foes by insisting on major cable news networks, “This Congress is not going to lift the embargo.”

On Oct. 28, the United National General Assembly adopted a resolution against the blockade for the 23rd consecutive year. The vote was 188 countries in favor and the U.S. and Israel against.

Kelman Cohen, who has made repeated trips to Cuba, its hospitals and the Latin American School of Medicine, said he believe the battle to get Heberprot into the U.S. will be neither easy or rapid, given the perceived political power of Florida’s Cuban-American community and its passionate support for the blockade.

“The Cuban-Americans are very powerful at influencing politicians,…and if they don’t want anyone doing business with Cuba, no business is done,” he said.

Nevertheless, the need for a medication like Heberprot, if it turns out to be safe and effective, is growing more important as the number of severe wounds continue to soar.

According to a study by Dr, Neal Barshes, with the Division of Vascular Surgery at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, the cost of treating severe diabetic wounds is more expensive than the five leading cancers in the U.S.

Yet, said Armstrong, who participated in the study, “we have only one FDA-approved pharmacologic to treat it, and that product has a black box warning,” the strongest warning label the agency requires.

The warning on Regranex cites an “increased risk of cancer death in patients who use three or more tubes of the product.”

At last month’s meeting, the institute’s scientists reported that more than 170,000 patients in 23 countries have been successfully treated with the Cuban drug, with 71 percent showing improvement.

“Their studies suggest, unlike other treatments using human growth factors, the potential for carcinogenesis from Heberprot is just about nil,” said Kelman Cohen.

The Cuban research institute did not respond to requests for a list of the countries using Heberprot.

Companies in France and the UK are said to be considering running clinical trials, but some physicians attending the December conference said the feeling was that most potential users and marketers of the medication will wait for trials to be conducted in the U.S.

While clinical trials are extremely expensive, the resulting FDA approval for new drugs is considered the gold standard by many physicians and pharmaceutical companies and adds enormously to the market value of the medication.

FairWarning contributor Andrew Schneider is a journalist specializing in public health issues. His email is investigate@mac.com.

FairWarning is a Los Angeles-based nonprofit investigative news organization focused on public health and safety issues.