State government workers are dwindling, leaving the Sunshine State’s most vulnerable people and resources at risk. (Photo by Sara Brockmann, via FLGov.com.)

This story was created in partnership with WGCU, NPR for Southwest Florida.

Editor’s Note: This is overview of the series Ashley Lopez, with WGCU public radio in Fort Myers and the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting, produced on how many state jobs have been lost in recent years, and the impact that is having on state services.

By Ashley Lopez

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

Over the last decade, Florida has shed thousands of state jobs, the consequence of a poor economy and a political philosophy at work. The result has affected how well agencies that protect everything from children to the environment can do their jobs.

According to a workforce report compiled by the state, while the nationwide average number of state workers per 10,000 in population was 211 in 2012, Florida had just 111 that year. That’s almost half the national average.

The state’s population has grown by 4 million since 1998. Its budget has increased by $25 billion since 2000. Yet Florida has almost 10,000 fewer established positions in the State’s Personnel System, State University System, State Legislature, Courts System and Justice Administration combined, than it did 15 years ago.

This means Florida’s government has been operating at its lowest staffing levels in almost two decades.

Even as the economy rebounds, state government isn’t growing with it.

This has largely been the result of a predominately Republican Legislature, and three Republican governors since the late 1990s – all of whom campaigned on promises to shrink government.

As a result, public agencies tasked with protecting vulnerable children, monitoring waterways and providing benefits to Floridians who have fallen on hard times, are struggling to fulfill their mandates.

Smaller By Design

Some of the most drastic public sector job cuts in the shortest amount of time were implemented during Gov. Rick Scott’s tenure.

Scott vowed to reduce government spending during his first gubernatorial campaign in 2010. He promised to cut the state workforce by 5 percent. And starting in 2011, when he was elected, he did.

In fact, Scott nearly doubled his promise. As of this year, Scott has reduced the state workforce by 9.6 percent, according to PolitiFact, a project of the Tampa Bay Times.

via FLGov.com

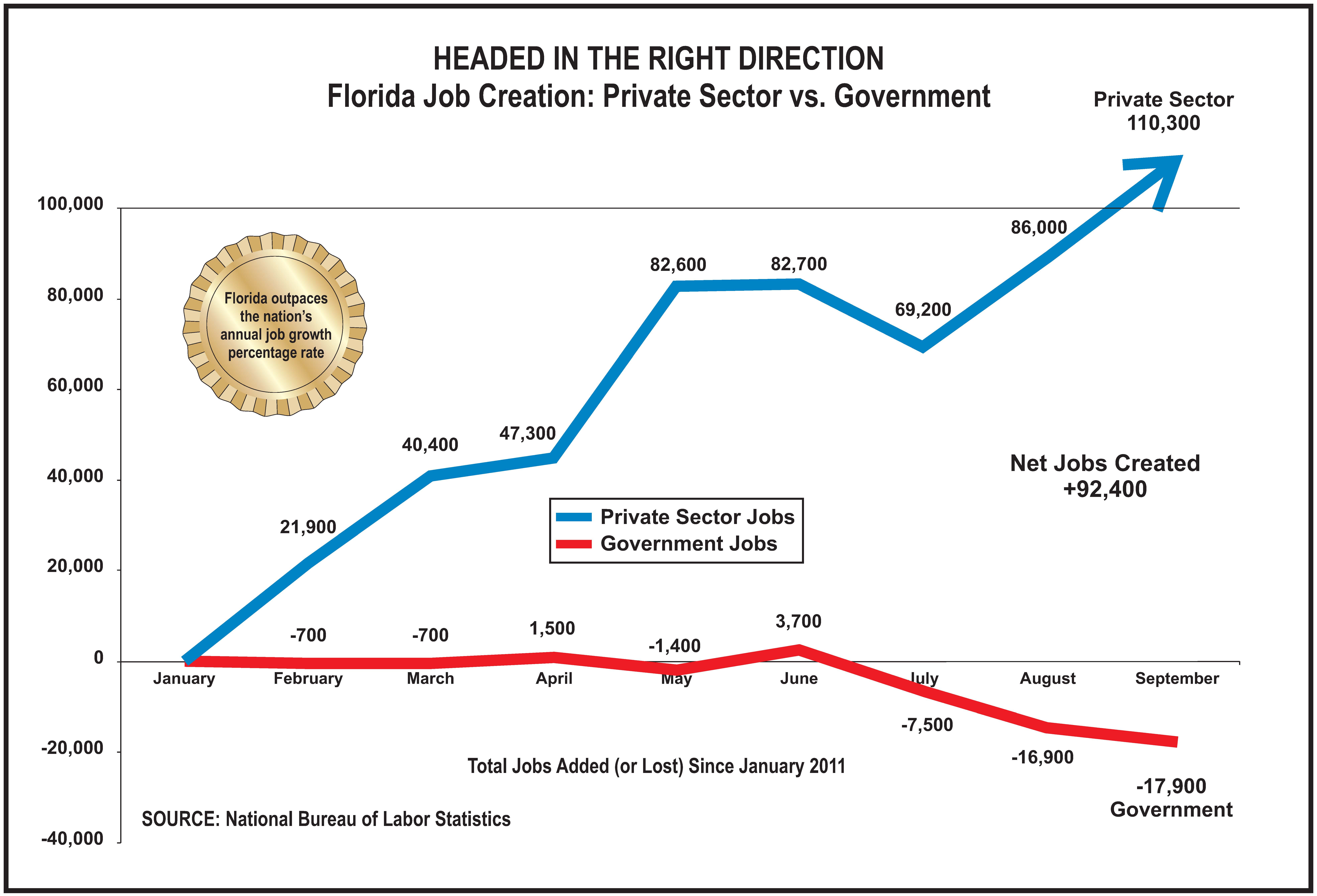

Scott is proud of this accomplishment. During a speech at a conservative political conference in Orlando in his first year in office, Scott boasted that the state’s unemployment numbers were shrinking faster than the national average because he was focusing on helping the private sector grow.

“We’ve generated 87,200 private sector jobs,” he said. Then he immediately bragged about hefty job cuts among the state’s public workforce.

“And we have 15,000 less government jobs in the state of Florida,” Scott said. “Government doesn’t create jobs.”

Not everyone thinks chopping away at state government jobs is a positive change.

“I worked in the state government for 30 years myself and looking at the reduction in staff in the state system over the years has been dramatic,” said Jeannette Wynn, president of Florida Council 79, part of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, a labor union.

Wynn said privatization and outsourcing of state functions has had real effects on several state agencies.

“They leave less employees to do the work that is left,” she said. “That means people are doing two or three people’s jobs. … Maybe where you had 10 people to do a job, now you have three people to do those duties.”

Dominic Calabro, the president and CEO of Florida TaxWatch, a non-profit that monitors government spending, said outsourcing and privatizing have made the state efficient.

Calabro points out that Florida’s government doesn’t have as much to do as other state governments because many services are handled by local government agencies.

“Florida has a lot of its functions to its taxpayer and citizenry directed through county budgets, school districts and municipalities and special local taxing districts,” he said.

Nick Johnson, of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, D.C., said many states have shifted state responsibilities to local governments, even as local budgets have experienced similar squeezes the past several years.

He said both local and state governments nationwide have been making cuts since the recession, which means a lot of important work is slipping through the cracks.

“Over the past six years, state and local governments combined have cut about 700,000 jobs,” he said.

Johnson said no government system is picking up slack for the other at this point, since the economic hardships of the past several years have affected everyone.

“Both the states and the localities have responded by cutting budgets, and that means cutting jobs,” he said.

More Than a Decade in the Making

Florida has a long history of state employee cuts that predate both Scott and the recession.

In the eight years Republican Gov. Jeb Bush was in office, Florida let go about 5,000 state workers. Bush was a small-government advocate who made slimming down the state system a priority, even though the state was not in a dire economic situation at the time.

Bush’s successor, Republican Gov. Charlie Crist, added back about 6,000 state jobs during his time in office, but he and state lawmakers shed just about all of them during the recession. The steepest cuts, however, came during the Scott administration.

State Sen. Eleanor Sobel, a Democrat from Hollywood, has been in the Florida Legislature during all three administrations. She said the state should be focusing on making its agencies better—not smaller.

“Downsizing is a simple way of trying to solve a problem and I don’t believe that’s the solution,” she said.

Child Protective Services

Florida’s Department of Children and Families (DCF) is the state agency under perhaps the most scrutiny for failing to fulfill its mission during the period of job cuts. In recent years, DCF has proven unable to monitor and protect many of the vulnerable children it is charged with protecting.

Miami Herald reporters Audra Burch and Carol Marbin Miller spent months sifting through nearly 500 child death reports filed by DCF, for the series “Innocents Lost.” The Herald’s key finding was that “after Florida cut down on protections for children in troubled homes, deaths soared [and] the children died in ways cruel, outlandish, predictable and preventable.”

The majority of the children who died were already on the state’s radar.

“It’s heartbreaking, and it’s also frustrating, because you feel like this didn’t have to happen– that so many of these deaths were preventable,” Burch said. In many cases children taken to the hospital after apparent beatings were later returned to their abusive parents.

This was a result of shrinking state resources at DCF, Miller said. One way officials cut costs was to adopt a new policy that kept families together despite signs of trouble.

“There was this policy that children were better off left with their parents even when they were — and they often were — in grave danger,” Miller said. “And the state wasn’t devoting the resources necessary to protect those kids who were being left with drug-addicted and mentally-ill parents.”

The result: 477 children died preventable deaths from 2008 to November 2013, according to the Herald.

One of the cutbacks at the agency was manpower, according to staff numbers from DCF. From 2003 to 2013 , the agency shed 12,000 jobs – shrinking the agency’s workforce by about 48 percent.

The Herald found direct links between the increase in preventable deaths and the staff cuts. DCF’s quality assurance team, an internal watchdog department, saw some of the most alarming cuts. Over five years the department responsible for making sure DCF was doing its job had its staff numbers cut by about two-thirds.

Gov. Rick Scott meets with child protective services following the Miami Herald‘s reporting on the agency’s failings. (Photo by Meredyth Hope Hall, via FLGov.com.)

“Why do we care about quality assurance? Those are the people you hire to make sure you don’t make the same mistakes over and over again,” Miller said. “Now, if you go back and you read 500 death reviews like we did, you will find that one of the things that has gone on here is that we have made the same mistakes over and over and over again.”

A DCF spokesperson said the steep job cuts reflect a move towards community-based care.

From 2000 to 2005 the state outsourced services for children who had been abused, neglected and/or abandoned to local non-profit organizations. The goal was to make child services in the state more effective and accountable, as well as save state government money. That’s not how things turned out, according to State Sen. Sobel, who chairs the Senate committee that oversees DCF.

“It is not true that this department has been running more effectively or efficiently or transparently,” she said.

Following the Miami Herald’s reporting this year, lawmakers passed a bill that funded 270 additional child protective investigators. DCF officials said in a statement that due to reform efforts, staff cuts no longer affect the agency.

But problems persist. In September, Donald Spirit fatally shot his six grandchildren—ranging in age from 2 months old to 11 years old—and his daughter, before turning the gun on himself in the small community of Bell. DCF had a lot of warning about the family’s troubles. Florida’s abuse hotlines received calls about the Spirit family starting in 2008, and DCF investigated 18 complaints about the family before the shootings.

“This is not just about DCF,” the Herald’s Miller said. “This is about every other agency in state government that performs social services or subsidized health care. And the dirty little secret about Florida politics is that we ration care for our most vulnerable.”

Environmental Protection

Responding to concerns about water quality, Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) officials held a public meeting in Fort Myers earlier this year. They asked local stakeholders which bodies of water they should monitor. For many in the room, this was a strange question.

Most of the crowd—a mix of activists, experts and business owners—said the state should be checking all of them.

“I think that DEP has an obligation to monitor every water to make sure that’s safe for its designated use for the public,” Jennifer Hecker of the Conservancy of Southwest Florida said at the meeting. “That is your agency’s role.” A local fisherman asked whether budget cuts were part of the reason DEP couldn’t monitor the entire state.

Nutrient-rich water pollutes the Caloosahatchee River in the summer of 2013, prompting frustration in the area. (Photo by Dale, via Creative Commons.)

“Yes, we have had budget cuts,” said Julie Espy, administrator of DEP’s Water Quality Assessment Program. “We have had position cuts.”

Espy then confirmed that those cuts had begun to affect her agency’s monitoring functions. Today, DEP has almost 500 fewer employees than it did in 1999.

“With that type of setup, the agency cannot be a regulatory agency—a respectable regulatory agency,” said Jerry Phillips, who works for Florida’s chapter of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. Phillips has been tracking enforcement action against polluters in Florida. According to his research, enforcement dropped by more than 83 percent from 2008 to 2013.

DEP officials acknowledge the decrease in regular caseloads, but have said in statements that this is due to higher compliance rates among potential polluters. Agency officials have also said the DEP is focused on preventing environmental harm before it occurs.

Phillips is skeptical of the explanation. “It really is a precipitous drop,” he said.

Help for Jobless Floridians

In another effort to cut costs, the state changed how Floridians file for unemployment benefits, only to find it didn’t have the personnel to keep up with the changes.

In 2011, Florida’s unemployment benefits system went through a $63 million overhaul. A new law mandated that all Floridians seeking benefits apply online in an attempt to modernize and streamline the state’s system. Immediately there were problems.

“They pretty much shut down the phone call centers as a means for applying for benefits overnight,” said George Wentworth, an attorney with the National Employment Law Project, which has been calling for a federal investigation into how problems with Florida’s unemployment system were handled.

Wentworth said there wasn’t a good plan in place to make sure the switch to a modern system went smoothly. To make things worse, the new online system—called CONNECT—was riddled with errors.

As soon as it launched, Floridians found it almost impossible to apply for help.

Via: Floridajobs.org

“What happened pretty much immediately after the launch of the CONNECT system was that really tens of thousands of workers stopped getting their weekly benefits,” Wentworth said. Some applicants went as many as 10 weeks without their unemployment checks. The backlog was due to CONNECT’s inability to automate the entire process. Many applications required a person to step in and make a decision, and with the budgets cuts, there were fewer people to make those decisions.

As the backlog grew, the state was forced to hire 250 people in three months to take on the work.

Despite failures like these that prompted state officials to hire back staff they previously let go, Scott and many state lawmakers have continued to focus their efforts on cutting Florida’s government.

This past legislative session the state had a $1.2 billion surplus—the first in several years. Proposals for spending the money included tax cuts and hometown projects like a military museum. Beefing up state agencies to pre-recession levels was not on the agenda.