Southbound traffic on Interstate 95 in Miami is at a standstill due to a traffic accident. The neighboring two express lanes are unaffected. (John Van Beekum / for FCIR)

By Eric Barton

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

In the next decade, Florida’s biggest cities will add toll lanes to the state’s busiest highways. Nobody knows exactly how much it will cost. Maybe as little as $3 billion. Maybe double that.

Media Partners |

What’s clear is that when the toll lanes across the state are complete, they will become one of the largest infrastructure projects in state history.

There’s little debate that these toll lanes, also called express lanes or managed lanes, make commutes quicker for those willing to pay as much as $10 to use them. But there has been little debate about the need for the projects – not one resident will cast a vote on the lanes or the billions spent to create them.

Instead, 169 miles of toll lanes will arrive as part of a Rick Scott administration initiative. A series of projects that will be under construction until 2021 will add multiple toll lanes in Jacksonville, Miami, Orlando, and Tampa.

An analysis by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting has learned that the toll lane projects began thanks to state-funded reports produced by a think tank funded in part by toll lane developers. In addition, Florida Department of Transportation Secretary Ananth Prasad used to work for one of the state’s largest toll lane builders before approving billions of dollars in toll lane projects, some of which have gone to his former employer.

Prasad says toll lanes effectively create a free market highway system, where only those who use them have to pay for them. “It’s about trying to efficiently move traffic,” Prasad said. “It’s about how we use existing lanes most efficiently.”

There’s little doubt the lanes can move cars, but what’s still to be decided is whether Florida commuters will be happy to see them.

Imported From Los Angeles

The idea of dividing a highway into free lanes and separate toll lanes might not exist if Bob Poole hadn’t moved from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles in 1986. Poole is founder of the Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank, and when he relocated, he suddenly realized how bad traffic could be.

Poole, an MIT-trained engineer, published a paper in 1988 about an idea he dreamed up to ease congestion. He proposed separating one or two lanes of traffic into an area where commuters would pay a toll to travel faster. Variable fees would go up as the highway becomes more congested, with supply and demand assuring that the toll lanes would always stay moving.

Then-California Gov. George Deukmejian, a Republican, liked the idea so much he pushed through plans to add toll lanes to State Route 91 east of Los Angeles. It made an immediate effect on commutes, Poole recalls.

“People were suddenly able to go the speed limit on one of the most congested highways in the country,” Poole said.

Since then, toll lanes have spread to many of the nation’s major cities, including Seattle, Houston, Dallas, and Minneapolis. In most places, they’ve been successful in reducing commute times for those who pay the extra fee, and in some instances, even for drivers in the free lanes.

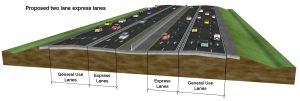

Photo courtesy of Florida Department of Transportation

There’s an economic and quality of life benefit to giving drivers a quicker commute, says Steve Polzin, the director of mobility policy research at University of South Florida’s Center for Urban Transportation Research. Toll lanes can be successful in cutting down wasted time spent commuting, Polzin said, and that makes a more productive society.

Toll lanes are also generally far cheaper than the $100 to $200 million per mile it costs to add commuter rail lines, Polzin said. Toll lanes, in comparison, typically cost $26 million a mile for the average four-lane “express lane.” And far more people are willing to use toll lanes over mass transit.

“We’re trying to provide mobility to the population, and this works,” Polzin said.

The idea of adding toll lanes in Florida didn’t begin until 2001. That’s when the Florida Department of Transportation called up Poole and asked for his help. Poole began working as a consultant for the state and moved in 2003 to the Broward County suburb of Plantation.

The state hired Poole to study the viability of toll lanes in South Florida. In 2008 he published a 38-page report titled “A Managed Lanes Vision for South Florida,” which would become a primer for toll lane plans across the state.

The report spelled out a future with toll lanes throughout the Miami metro area by 2030. Poole imagined an 852-mile toll lane network that could eliminate about a third of the region’s wasted hours spent in congestion. The report does not estimate the cost of all those toll lanes, but based on present-day estimates, the plan would cost about $22 billion.

In total, the state paid Poole $34,905 for his report and other work, according to the FDOT. That’s in addition to the $200,000 yearly salary he makes from the Reason Foundation, according to tax documents.

After Scott’s election in 2011, the governor tapped Poole as a transportation advisor for his transition team. A year later, Poole wrote a second report that envisioned a future of toll lanes intersecting Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties. That report – funded by the Reason Foundation, not state money – proposed 579 miles of new toll lanes at a cost of $11.4 billion.

What wasn’t mentioned in the reports is that Poole’s Reason Foundation receives funding from several companies that stand to benefit from the toll lane projects he has proposed. Poole’s think tank has accepted money from oil companies, car manufacturers, and several construction companies that build toll lanes.

Among them is ACS Infrastructure Development, an international corporation with an office in Coral Gables. The company now manages the Interstate 595 toll lanes and is building new toll lanes on Interstate 75.

Poole says the money given to his think tank is irrelevant. “We do the work we do because it makes sense,” he said. “We have never done a project because someone has given us money.”

Toll lanes in Florida got a second boost after Scott’s election, when the governor brought in Ananth Prasad as his secretary of the Florida Department of Transportation.

Prasad had been a longtime employee of FDOT. He left in 2008 to join HNTB, the Kansas City-based construction company that specializes in infrastructure projects including toll lanes. Prasad spent two years as a vice president in HNTB’s office in Tallahassee, in charge of relations with FDOT on multiple state-funded projects.

HNTB, with seven offices in the state, has deep ties politically in Florida. Its political action committee, HNTB Holdings Ltd. PAC, amassed $397,000 in contributions since 2013. It contributes to mostly conservative candidates, including $25,000 to the Republican Party of Florida and $25,000 to a political action committee that’s working to reelect Scott.

As secretary, Prasad quickly began pushing through toll lane projects. His office approved new toll lanes in Jacksonville, Tampa, Orlando, and the three counties that make up South Florida.

Just how much the toll lanes will cost hasn’t been tallied. Because the toll lanes are typically installed as part of other highway improvement projects, the Florida Department of Transportation was unable to provide a breakdown of the costs. But based on average prices of toll lane construction, Florida could be looking at spending about $4.4 billion.

Poole told the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting that the price tag for the toll lanes could cost as much as $6 billion. He cautioned it could go up significantly if the lanes include flyovers, bridge repairs, and other costly infrastructure upgrades.

At those prices, the toll lanes would become one of the largest infrastructure projects in Florida history, said James Clark, a historian and lecturer at the University of Central Florida. Even in today’s dollars, the Kennedy Space Center cost less, as did Florida’s Turnpike; draining the Everglades likely cost more, although there’s no known total for the price of that decades-long project.

What a proposed toll overpass would look like. (Photo courtesy of Reason Foundation.)

In an interview with the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting, Prasad said he had the governor’s full backing for the projects, as long as they didn’t raise taxes. Instead, the plans are generally funded through bonds that are paid off by the tolls that are collected. Those bonds will multiply the costs of the projects. In Broward County, the Interstate 595 toll lanes were part of a $1.8 billion project; when the bonds are paid off in 10 years, it will cost about $4 billion more.

Prasad said his only motivation for approving toll lane projects is that they are the best way to move traffic quickly. Asked about whether his time at HNTB might have influenced his support of toll lanes, Prasad said: “Two years at a transportation firm doesn’t trump 20-plus years with the DOT. That is a far-fetched theory.”

Scott, through the governor’s press office, declined to be interviewed for this report. Scott’s press secretary, John Tupps, emailed this response: “Governor Scott is proud to have invested a record $10.1 billion to improve Florida’s transportation infrastructure in the It’s Your Money Tax Cut Budget.”

Florida’s Toll Lane Future

At the local level, cities and counties generally have to ask voters for permission to build major infrastructure projects. But FDOT has generally moved through the toll lane projects without referendums.

Local transportation authorities have been asked to weigh in and have held public meetings, but the plans have largely moved through exactly as FDOT designed them.

In at least one instance, the completed plans looked far different than what was promised to local transportation officials. In Miami, original FDOT designs of the I-95 toll lanes called for multiple exits and entrances, allowing commuters throughout Miami-Dade’s northern corridor to access the lanes. When built, they included entrances and exits only at the far end of the lanes, meaning they largely benefit commuters traveling to or from Broward County.

Joe Quinty, a regional planner at the South Florida Regional Transit Authority in Pompano Beach, likened it to a bait and switch. “It’s completely different from what was approved, and I can’t believe people in Miami-Dade aren’t up in arms about it,” Quinty said.

Quinty says the state’s toll lane plans have been rushed through the typical approval process, allowing for little input from anyone outside FDOT.

“These plans have been proposed, drawn up, and approved at a speed you don’t usually see in government,” Quinty said. “People have got to be wondering, ‘Why don’t I have more of a say in all of this?’”

In Jacksonville, the state is building a pair of toll lane projects that will total 29 miles. The plans come despite a referendum Jacksonville voters passed in 1988 to rid the city’s highways of tolls in exchange for a half-cent sales tax. FDOT administrators say the state doesn’t have to abide by the local referendum.

Tommy Hazouri, who was mayor at the time, says the state’s plan to add toll lanes violates the spirit of the referendum. Locals will continue paying the sales tax even after the addition of the toll lanes.

“It’s not just distasteful. It’s dishonoring what people voted for,” Hazouri said. “It’s an issue of honoring what you say. Voters decided to tax themselves to get rid of the tolls, and here we are adding tolls. It flies in the face of public trust.”

Some critics of toll lanes claim they create “Lexus lanes,” where rich drivers get to speed past those who can’t afford the tolls.

That claim seems to have been supported by a state-issued report on toll lane drivers, which found that 87 percent of motorists who use the lanes most frequently have an annual household income of more than $76,000. Of those, the people who use the lanes most frequently have household incomes of at least $150,000, three times the median household income in Florida. The least frequent user are the poor, those whose household income is less than $25,000, who account for 4 percent of toll lane drivers.

A Lexus drives in an express toll lane in Miami. Some critics call the toll lanes “Lexus lanes.” (Photo by John Van Beekum / for FCIR)

Poole disputes the idea that the toll lanes become Lexus lanes and says the average cars driven by these drivers are affordable – Toyotas, Hondas, and Chevys. He says the lanes give all drivers a chance to get somewhere when they’re in a hurry.

As for whether the money being spent on toll lanes could be used on mass transit, Prasad, the transportation secretary, says commuter rail lines don’t do enough to ease highway congestion.

“People say, ‘What about me? I’m stuck in traffic today?’” Prasad said. “Those who are against this do not have to use them. The consumer is ultimately in control.”

With no referendum or public vote coming, whether Florida commuters will like the idea of express lanes likely won’t be known until they’re actually built.