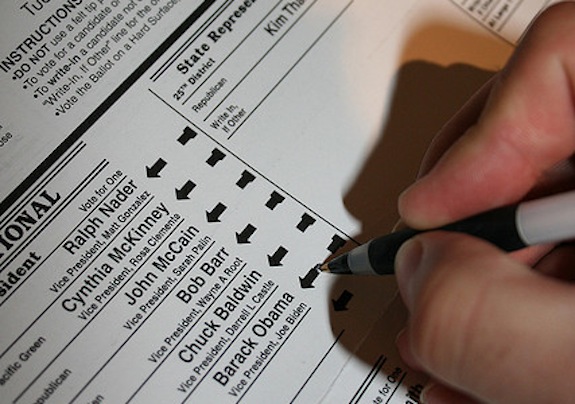

The ACLU of Florida announced that more than 13,000 Floridians had their voting rights restored, but may not know it. (Photo by Gary Jungling.)

By Ashley Lopez

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

More than 13,000 felons in Florida may not know their voting rights have been restored.

That’s because the state hasn’t notified them.

Through a public records request to the Florida Parole Commission, the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida found that 17,604 certificates announcing that someone had his or her voting rights restored were not delivered. Of the 17,604 intended recipients of these certificates, 13,517 have not yet registered to vote.

When someone is convicted of a felony in Florida, voting rights are revoked. Under Gov. Rick Scott’s administration, after a felon finishes his or her sentence, her or she must go through a 5 or 7 year process and can only get restoration from the Board of Clemency. Once rights are restored, the state is supposed to notify these individuals.

According to the ACLU:

The RCR certificates returned as undeliverable may have already resulted in keeping as many 13,517 citizens from voting in the August 14 primary. Unless they are notified soon that their voting rights have been restored, these same citizens will also lose their right to vote in the presidential election this November, which requires that they first to register to vote by the October 9 deadline.

Rights restoration has long been an ugly mark on Florida’s voting rights history — and the state doesn’t seem to be improving.

The NAACP released a lengthy voting rights report last year that found Florida is among the states with the “most restrictive” felon disenfranchisement laws. According to the group, this was just one of many aspects of the state’s voting practices that will limit voter participation among minorities in the upcoming election.

According to the report:

Florida imposed a mandatory five-year waiting period and petition process for the restoration of rights for individuals who have completed their sentences. In March 2011, Florida, which already had the largest disfranchised population of any state in the country (approximately 1 million), rolled back state rules enacted four years ago that eliminated the post-sentence waiting period and provided for automatic approval of reinstatement of rights for individuals convicted of non-violent felony offenses.

The previous rule was put into effect in 2007, allowing the restoration of rights to more than 154,000 people who had completed their sentences.

Under Florida’s new rules, all individuals who have completed their sentences, even those for non-violent offenses, must wait at least five years before they may petition the Clemency Board for the restoration of their civil rights, including the right to register to vote. Some offenders even have a mandatory seven-year period before they may petition.

Even worse, the five–year waiting period for individuals convicted of a non-violent offense to apply for restoration of voting rights resets if a person is simply arrested for a criminal offense—even if charges are eventually dropped or the person is acquitted of all allegations.

By most accounts, these new clemency rules make Florida’s the most restrictive felon disfranchisement approach in the country.

It is also worth noting that getting your rights back after a felony conviction has been historically difficult. There are also many ways in which these folks are being kept from the polls, even after they do their time.

Slate’s Dave Weigel pointed to some old reporting a few weeks ago that highlights a pretty interesting barrier for former convicts: “In Florida, for example, home to around a quarter-million black men with felony convictions, the new-old rules force ‘any former felon who wanted to regain voting rights to appeal directly to the governor.’ ”

This means these folks have to ask for their rights back, which, as Weigel points out, can be a pretty humiliating process. According to a 2004 Vanity Fair story titled “The Path to Florida,” writer David Margolick and a team of reporters attended one of these voting rights-restoration hearing for Beverly Brown, “a black Miamian who has been applying for seven years.” During the hearing, Brown had to ask then-Gov. Jeb Bush for her rights back so that she could get a state license required for a job. In the course of this hearing, she was inexplicably asked by the state CFO what “wailing rock cocaine” was.

She was never charged with having “wailing rock cocaine” in her possession and she had to explain that she did not know what that was.

The Guardian in the United Kingdom is doing a series on voting rights and Florida, as the election nears. One of their stories explains that Gov. Rick Scott has carried on this legacy for the state. According to the Guardian, “one of the first acts of [Scott] when he took office in 2011 was to reimpose what is in effect a lifelong voting ban on anyone convicted of a felony — including 1.3 million Floridians who have fully completed their sentences.”