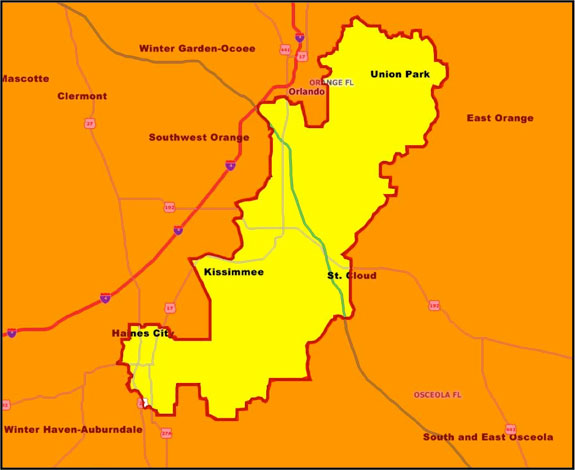

Latino Justice submitted a proposed district map in Central Florida that includes parts of three counties -- Orange, Osceola and Polk. (Photo courtesy of Latino Justice.)

By Ralph De La Cruz

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

Members of South Florida’s ethnic media gathered in Miami Oct. 6 to hear about the complexities of “compactness, contiguity, and communities of interest” — the defining principles of redistricting.

The entire country is in the midst of the once-a-decade process that sets the political boundaries for everything from Congressional districts to school board and water management districts. The Miami meeting was the eighth such briefing that New America Media has conducted nationwide.

About 20 reporters, editors and publishers — from small tabloids, online publications, television networks and traditional newspapers — heard about the history of redistricting and the complexities of trying to ensure some sense of fairness in the process.

“Beauty matters,” panelist Juan Cartagena, president and general counsel of LatinoJustice PRLDEF, said, referring to “compactness,” one of the three things courts examine to determine the legality of a district. Compactness refers to a desire to avoid serpentine, irregular-shaped districts.

“Districts that look nice usually get approved,” Cartagena said. “Districts that look weird are suspect.”

Another defining term, “contiguity,” means that any part of a district cannot be geographically separated from the rest. And “communities of interest” refers to keeping together groups with similar self-interests. Depending on the community, they could be tied together by race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status or geography.

“In Miami, ethnicity is more important than race,” pointed out Badili Jones of the Miami Workers Center and Florida New Majority.

It’s easy to imagine how just those three goals could create conflicts and complexities.

Redistricting is at least partially instructed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibits any voting practice that has a discriminatory effect. And in Florida, redistricting is further complicated by the Fair Districts Amendments, which voters passed last year.

Amendments 5 and 6 stipulate that new districts not favor, or punish, a particular candidate or party and that districts follow natural geography whenever possible. It’s an attempt to prevent the political manipulation, or gerrymandering, of districts by state lawmakers who often have interests in how the districts are drawn.

“Redistricting is about power, control and influence,” said Leon Russell, legislative chair of the Florida NAACP and vice chairman of the national NAACP’s board of directors. “The question we have to answer is: How do we gain some of the influence, some of the power, and at least a little a little bit of the control?”

One of the concerns expressed by speakers was that, although lawmakers held redistricting town hall meetings throughout the state, they did not reveal any maps that may be under consideration. They also did not speak or offer any opinions at the meeting — something that data expert John Garcia of LatinoJustice called “an official, or unofficial, gag order.”

With the end of the statewide tour by legislators, and so much focus on Congressional districts, voters may not realize that the redistricting process continues for an array of other districts. Redistricting is about more than just Congressional districts.

“Redistricting touches everything all the way down to the water management board,” Cartagena said. “Miami-Dade (County Public) Schools have not even started their redistricting process.”

Floridians can obtain redistricting information online at floridaredistricting.org.