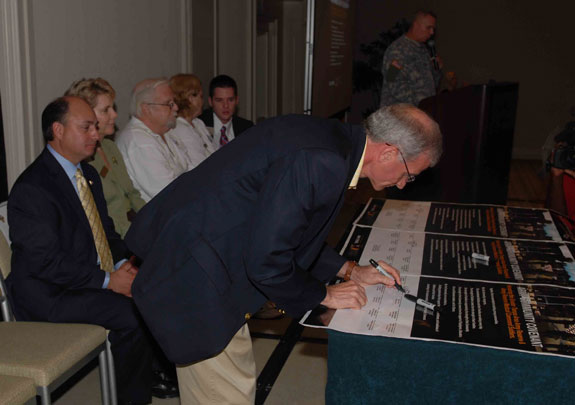

State Sen. Mike Fasano signs the Army Community Covenant in Tampa. Fasano recently received a $10,000 bill for records from the State Board of Administration. (Photo by U.S. Army Sgt. Eric Jones.)

By Ralph De La Cruz

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

The St. Petersburg Times was investigating an investment made by the State Board of Administration, which runs the Florida pension fund. Keeping an eye on the SBA’s investments is probably a good idea, considering the SBA controls $145 billion in Floridians’ assets.

The Times wanted information about a mere $125 million. It was money that had been invested in a hedge fund connected to a former client of SBA chief Ash Williams.

Considering the relationships and the amount of money — not to speak of the fact that it’s Floridians’ money and their agency — it’s not surprising the Times was interested enough to file a public records request for documents relating to the investment. And after all, Florida has among the best open records laws in the country.

The Times made its request in July 2010. It was promptly denied. The SBA said they couldn’t give out that information because the deal was still being worked out.

In April, Sydney Freedberg, the Times reporter investigating SBA’s investments, was writing about how the SBA was pushing for renewal of an exemption to public records law for much of its business.

“A lot of that information needs to remain confidential, as is the norm throughout the investment world,” Williams told an investment group.

Freedberg wrote about how, under Williams, the SBA had expanded the reach of a 2006 law that allowed exemptions for “proprietary confidential business information.” Eventually, companies were operating under the honor system. All they needed to do was label something as “confidential” and it was no longer a public record. The flurry of denied public records requests and extremely-redacted records was predictable.

Freedberg reported that in March alone, the SBA refused to release 13 audit reports and three customer satisfaction surveys for Bank of New York Mellon — the bank that protects Florida’s fund. When the newspaper requested information about a private equity deal with a group called Liberty Partners, the SBA released a 124-page report — and 115 of those pages were blacked out.

Almost a year later, in June, the newspaper decided to solicit the help of one of their local senators: hard-hitting, independent-minded Mike Fasano, a Republican from New Port Richey.

Fasano has spoken out against corruption among his colleagues, and opposed party leaders as if they were mere mortals. When Gov. Rick Scott and Republican legislative leaders pushed for property insurance reform that would give insurance companies the opportunity to hike rates, he spoke out. When they pushed for prison privatization, he spoke out. When they shut down a prescription pill database, Fasano said Scott’s decision was “beyond my understanding.”

“He’s become the Republican version of Claude Pepper,” one politician told the Times earlier this year.

So populist Fasano, the defender of the “little guy and gal,” sent a public records request himself. Williams responded they get together and he could quickly explain everything.

After Fasano persisted in getting the public information he requested, he received an invoice that estimated the costs for fulfilling the request at …

… $10,750.

And thirteen cents.

Fasano fired off a letter to Scott, Atty. Gen. Pam Bondi and Chief Financial Officer Jeff Atwater. The three oversee the SBA. And all three reportedly knew about the SBA’s response to Fasano.

“My first concern is why should it take months to share information that should already be at the SBA’s fingertips,” Fasano wrote.

And then he really got to the heart of the matter:

“Secondly, as a state senator, I am being given an invoice for $10,000 to pay for information pertaining to Florida’s investment decisions. What would it cost a private citizen who may request the same information?”

Fasano got no response from Scott. Bondi said she’d check into it. Atwater’s office told Freedberg that Fasano should speak to the SBA.

“As this issue drags on,” Fasano told the Times, “it is hard not to come to the conclusion that someone has something to hide.”

We’ll keep you private citizens posted on the request and the investigation.