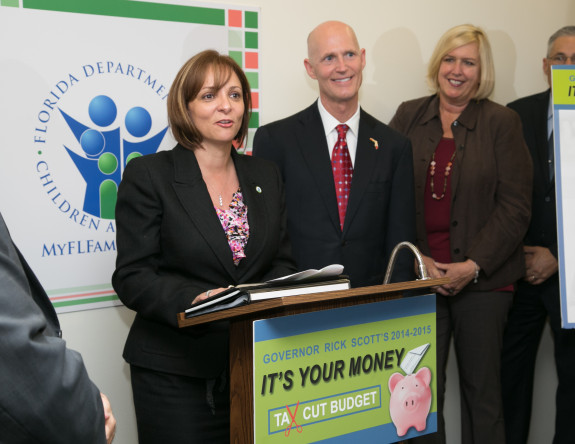

Officials at the Florida Department of Children and families defended the agency’s transparency and new death review report to state legislators. (Photo via FLGov.com)

By Ashley Lopez

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

State lawmakers grilled child welfare officials this week about troubles with child death reports coming out of their agency.

Last year, The Miami Herald published its “Innocents Lost” series, which is a heartbreaking and thorough look at the state’s troubled child welfare system. The massive public records project chronicled 477 deaths that happened under the Florida Department of Children and Families’ (DCF) watch since 2008.

As scrutiny of DCF increased, reporters noticed some changes at a particular branch of the state agency. According to the Herald, “records show, child abuse investigators in the Southeast Region’s five counties ceased filing child death incident reports, which are required by DCF policies.”

They found evidence the branch began hiding a paper trial of 30 children’s deaths when the newspaper started reporting on the agency’s failures.

Later that month, a grand jury scolded DCF for under-reporting child deaths in the state related to abuse or neglect.

Now, however, officials are defending their practices.

According to The Miami Herald this week,

Florida’s top child welfare officials were on the defensive before a House committee on Wednesday as they defended an annual report on child deaths that had been stripped of data and embarrassing details about the state’s role in failing to protect the children whose lives were lost.

Secretary of the Department of Health John Armstrong told the House Committee on Children, Familes and Elders outlined the membership, duties and terms of appointment for the state Child Abuse Death Review Committee’s which, by law, must provide an analysis of what killed Florida children the year before.

But unlike previous years, which was nearly 200 pages long and included dozens of charts and graphs describing both the victims and perpetrators of child abuse, and brief memorials for several of the youngsters whose lives were cut short, the 2014 report was only 17 pages long.

The scaled-down death report came the same year the Miami Herald’s series Innocents Lost detailed the deaths of 477 children whose families were known to the Department of Children & Families.

“Ultimately, recommendations are only as good as the quality of data and analysis,’’ Armstrong told the House panel. He then introduced the chairman of the death review committee, Robin Perry, to explain the report.

The committee also heard from Department of Children and Families Secretary Mike Carroll.

According to the Herald,

He said that as a result of legislation passed last year, Florida’sa child fatality web site is the most extensive in the nation.

“I don’t think we can get more transparent on child fatalities than we are,’’ he said.

He defended the department’s extensive redactions of its child death reports, saying that when pages blacked out it is often because they are trying to protect siblings who are still alive.

He said that the predominate cause of child deaths are drownings and unsafe sleep, and nearly all unsafe sleep situations involve a child under age 1 and a parent with drug or mental health issues.

The Florida Legislature, following the Innocents Lost series, enacted some reforms and beefed up spending at the agency.

But even after legislative efforts, problems persist.

The Herald’s Carol Marbin Miller reported at the time,

“Nothing has changed,” said former Broward Sheriff’s Office Cmdr. James Harn, who supervised child abuse investigations before retiring when a new sheriff was elected last year. “Some day, somebody will say ‘let’s just stop the political wrangling.’ Here’s what you’ve got to do: Just tell the truth.”

For several years, BSO, which has investigated child deaths under contract with DCF, has recorded significantly more fatalities due to neglect or abuse than other counties, where DCF does its own investigations. One important reason for the disparity is that the sheriff’s office long has insisted that drownings and accidental suffocations — among the leading causes of child fatality — be counted, while DCF has, in recent years, declined to include the majority of those in its abuse and neglect tally.

As a result, said Harn, the statewide numbers “are cooked.”

“It’s not going to get fixed as long as they want to hide things,” Harn added.

A DCF spokeswoman in Tallahassee, Alexis Lambert, said the agency studies all child fatalities — not just the ones it verifies as resulting from abuse or neglect — to “improve and strengthen child welfare practice and services provided to vulnerable children and at-risk families statewide.”

She added: “The safety and well-being of Florida’s vulnerable children is DCF’s top priority. Understanding and assessing child fatalities is one way the department analyzes the issues facing families and develops strategies to meet the needs of struggling families and protect vulnerable children.”

Campaign politics were commonly blamed for why child death stats in Florida weren’t telling the whole truth.

State lawmakers have vowed to continue addressing how the agency is protecting the state’s most vulnerable children.