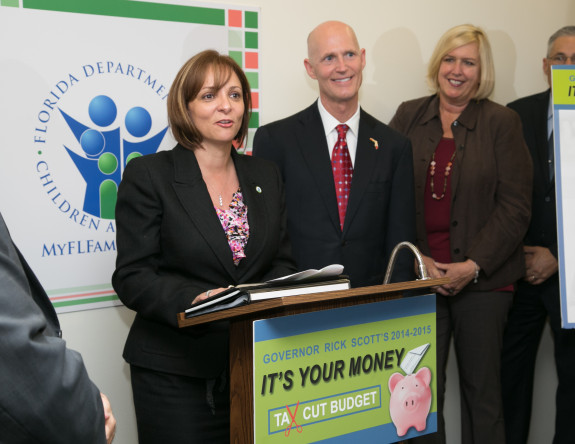

The Miami Herald found officials at a branch of DCF hid reports of more than two dozen child deaths. (Pictured above: former interim DCF Chief Ester Jacobo and Gov. Rick Scott. Photo via FLGov.com)

By Ashley Lopez

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

According to The Miami Herald, a branch of the Florida Department of Children and Families began hiding a paper trial of 30 children’s deaths when the newspaper started reporting on the agency’s failures to prevent hundreds of deaths of children it was monitoring.

The Herald’s “Innocents Lost” series is a heartbreaking and thorough look at the state’s troubled child welfare system. The massive public records project chronicled 477 deaths that happened under DCF’s watch since 2008.

However, reporters working on the story found later that their investigation spurred some changes at a particular branch of the state agency. According to the Herald, “records show, child abuse investigators in the Southeast Region’s five counties ceased filing child death incident reports, which are required by DCF policies.”

The paper reports that the agency hid reports of drowning, smothers and murder-suicides, among other things.

The Herald reported this weekend:

Documents obtained after Innocents Lost was published show that starting at least as early as last November, as the Herald was grilling DCF on its problems in preventing the deaths of children under its watch, one branch of the agency deliberately kept as many as 30 deaths off the books — ensuring they would not be included in the published tally.

The incidents were in DCF’s Southeast Region, encompassing Palm Beach, Martin, St. Lucie, Okeechobee and Broward — the county cited by the Herald as having the most reported deaths by abuse or neglect.

DCF’s new secretary, Mike Carroll, said he has dispatched his top deputy, Pete Digre, to look into the missing records.

Carroll’s initial assessment of the matter: “Was it ill-advised? Absolutely. Was it a mistake? Absolutely.”

But as to whether the missing records amounted to a deliberate attempt to conceal deaths or suppress numbers in a series of articles highlighting DCF blunders, Carroll said: “I am not certain yet. I hope that’s not the case. I have made it clear to folks that we are not in the business of hiding information.”

Southeast Region administrators say they ceased filing the required reports for at least five months because they were in the process of developing a new reporting tool, Carroll said.

He added: “There is no evidence that makes me think there was a conspiracy to withhold information. … I don’t have anything that shows me this was done with ill intent.”

The first round of reporting from the Herald included incident reports from 2008 until November 2013. However, months after the project was published, reporters wanted to look at the most recent incident reports, which were filed after the paper started work on its series.

What the Herald found is that the Southeast region of DCF stopped filing incident reports altogether, even though “more than two dozen child deaths had occurred in the region, according to the state’s child abuse and neglect hotline,” the paper reports.

On April 2, a DCF child abuse and quality assurance specialist, Leslie Chytka, wrote in an email that she had found 30 child deaths with no corresponding incident reports — a violation of agency rules that say such reports must be completed “within one working day” of a child’s death. She instructed staff in the region to file reports for all of the 30 deaths.

That led to another email, from another staffer, with the title: “the upcoming rash of incident report deaths.” In it, DCF quality assurance manager Frank Perry wrote: “Disregard the next thirty or so incident reports that will be posted in the next day or so. They are child deaths we are aware of but are not in the … system. I have been asked to create these incidents so they are recorded.”

And create them he did — very quickly. The reports, filed by Perry on April 3 and April 4, are unlike any of the 145 or so the Herald received from the rest of the state at that time: They were largely devoid of information. Many of the Perry reports consisted of four sentences or fewer and offered no information, or scant information, regarding each family’s history with DCF. Such information is customarily provided in an incident report.

The Innocents Lost project was the catalyst for bills in the Florida Legislature this year that reformed the state’s child welfare system.