Tallahassee attorney David Moye said attempts to dismiss the lawsuit are “unprecedented.” (photo by Mark Wallheiser)

By Tristram Korten

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement’s troubled five-year-old automatic fingerprint identification system (AFIS) has cost far more to maintain than it did to design and build because of technical problems. It is now so unstable that it is causing delays during investigations and arrests across the state.

A former engineer for Motorola, the company that built the system, has come forward and claimed the company delivered a product riddled with problems. His claims are documented in internal Motorola reports that he said were never shared with the FDLE.

Media Partners |

Documents reviewed by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting detail a series of costly maintenance requests and upgrades needed to keep the fingerprint system functioning properly. The documents also include internal Motorola reports recording accuracy issues with the fingerprint system. If true, in addition to delaying investigations, these problems could mean suspects weren’t identified during system searches, and criminal cases using some fingerprint evidence could be called into question.

FDLE contracted Motorola in 2007 to build the $7.4 million system. The contract was sole source, meaning no other companies bid on it. Almost immediately after its completion in June 2009, officials asked the Florida Legislature for money to address maintenance and technical support issues.

By December of 2012, the FDLE had spent an additional $9.2 million on the system, far more than the department’s estimated maintenance budget.

But they did not solve the problems.

In October, FDLE officials submitted a request for another $2.1 million for new software. FDLE officials wrote at the time: “While still functional, the system is not performing at optimal or supportable levels. As a result, system users are experiencing significant delays processing arrests and latent print searches in support of criminal investigations. Additionally, the system is not performing in a stable manner and requires frequent restarts of integral components.”

FDLE blames the problems on increased demand and usage. But the instability and delays echo issues that Motorola engineers documented in reports while testing the system in 2008 and 2009. Those reports were never shared with FDLE, according to Zoltan Barati, the former Motorola engineer.

An FDLE spokeswoman stated that the system’s problems have nothing to do with Barati’s allegations and “it would be inaccurate to report that.” The budget requests have “been in line with FDLE expectations,” she added.

Barati said he complained to his employer about quality control issues and then was transferred off the project and eventually fired in 2009. Before he was fired he downloaded the internal reports recording poor performance.

At the time Motorola was in the final stages of selling the biometric unit to the French firm Sagem Sécurité.

Barati has filed a whistleblower lawsuit against Motorola in Florida’s Second Judicial Circuit in Tallahassee, alleging that the state was defrauded. Sagem is not named as a defendant. Citing the pending litigation, Motorola Solutions, Inc., through spokesman Steve Gorecki, declined to comment.

The FDLE’s lax oversight contributed to the problem, according to Barati. The department’s “project managers became more and more forgiving, and were not following up on issues like they should have been,” Barati said in a telephone interview from his native Hungary, where he returned after losing his job. “All in all, Florida was just taking what was given to them.”

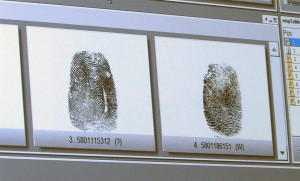

The most critical problems the internal reports document were related to the system’s accuracy rates and response time. During two years of testing, the system did not meet the required 99.9 percent accuracy the FDLE contract required when comparing what’s known as tenprint, the impression of all 10 fingers made by ink, to tenprint records in the system. That meant the system was missing as many as 13 prints in a batch of 1,300, which could add up to hundreds of prints in a day.

The system also did not meet the 98 percent accuracy rate for latent prints, which are partial prints lifted from crime scenes. The system was also not meeting the 550 matches per hour the contract required when searching tenpritns, in the months before the contract was completed.

If the ability of the AFIS to compare and match fingerprints is compromised, it could mean that biometric data entered by police trying to identify suspects, as well as employers conducting criminal background checks, including people supervising children, could have produced inaccurate results by missing fingerprints in the system. Motorola engineers recorded one episode of a false positive hit during testing, a worst-case scenario for law enforcement.

The MorphoTrak, formerly Printrak, fingerprint identification system. (Photo courtesy Sarasota County Sheriff’s Office.)

Motorola and the FDLE deny Barati’s claims. A year ago, FDLE officials said there were no outstanding problems with the system, and that the expenses were regular maintenance and upgrades. The contract, however, estimates that routine maintenance would be $835,000 a year, or $2.5 million through 2012. The state is scheduled to spend nearly 5 times that number on maintenance. Motorola was not obligated to share the internal reports, according to the FDLE.

Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi is aggressively trying to dismiss the lawsuit. Bondi’s move comes even though the state is not a party and even though the state may benefit financially if the company is found to be negligent.

Because Barati filed his lawsuit under the False Claims Act, on behalf of the State of Florida, the Attorney General’s Office argued it has the right to seek dismissal. Bondi’s office asked an appeals court to dismiss the case with prejudice and to prevent the presiding judge from ruling on its motion to dismiss. Barati’s Tallahassee attorney, David Moyé, who specializes in False Claims Act whistleblower cases, said the state’s vigorous efforts to unilaterally dismiss the case are unprecedented.

“In all my years practicing in this area of the law I have never seen anything like this,” he said.

But the state maintains that nothing is wrong. A Sept. 13, 2012, report by the FDLE’s Inspector General’s Office reviewed Barati’s complaint and found no problems with the contract. The four-page report concluded that Motorola fulfilled its end of the contract and that the system “exceeded expectations,” according to unidentified “subject matter experts” the FDLE interviewed.

Those experts told the Inspector General’s Office that “the number of mistakes/errors in fingerprint identification has dropped drastically since the implementation of the new AFIS,” according to the report. “The number of fingerprint matches by FDLE’s Crime Lab has increased 300% since the implementation of the new AFIS.”

The FDLE report does not provide any data confirming this assessment and does not address Motorola’s internal documents showing several failed tests on accuracy and processing speed. The report also does not state whether FDLE knew about specific system failures when it took possession of AFIS. FDLE officials did not return emails requesting comment.

The FDLE’s “team lead” on the project, Charles Schaeffer, filed an affidavit in April on behalf of Motorola defending his monitoring of the project. “At each level of testing the contract required, FDLE’s test team was present,” Schaeffer stated. “Therefore, the test team saw, in real time, the testing results and was knowledgeable and conversant in their import.” Schaeffer stated he did not know and had never spoken to Barati, who worked in Anaheim, Calif.

One reason the state might want to have the lawsuit dismissed is that a faulty fingerprint ID system could be a legal headache for Florida law enforcement agencies, according to Tamara Rice Lave, associate professor at the University of Miami School of Law, who specializes in criminal evidence law. If fingerprint evidence is used to prosecute a defendant, and the system’s accuracy is faulty, prosecutors may be obligated to reveal that information to defense lawyers, who can use it to discredit the evidence against their clients.

In a worst-case scenario prosecutors would have to re-examine all cases where fingerprint and palm-print evidence was used to convict someone since the system was put in place, Lave said.

“This suit has the potential impact to reverse all convictions that rely on fingerprints using this system from inception to present,” she added.

That would be more likely to happen if the system were shown to make false-positive matches, which is uncommon. Motorola engineers recorded one incident of the AFIS making a false-positive match during testing. But it has happened in the real world. In 2004 the FBI arrested an Oregon attorney based on fingerprint evidence that linked him to a terrorist bombing in Madrid. The fingerprint match was a mistake; the lawyer was exonerated and won a $2 million settlement.

The probability of a false hit is very rare, according to Cedric Neumann, a forensic scientist and assistant professor of statistics at South Dakota State University, because if a system makes an automatic match, human analysts often are required to review it. “Once in a while there is a series of mistakes and a plane crashes,” Neumann said. “It doesn’t mean we don’t fly.”

Barati, who joined the company in 1995 and was promoted in 2004 to principal staff software engineer, was working on merging the Printrak 10.0 system with version 10.1, which FDLE was purchasing. In 2008 he complained to superiors that the company was not adhering to industry standards meant to protect code after it was written. Nothing was done, he said.

As he continued working on the FDLE project, Barati said he became alarmed that Motorola was not sharing internal tests showing critical system failures, as the contract required. “Our internal tests showed we were way off,” Barati said. “Particularly, the accuracy requirements and response time requirements.”

The contract required the fingerprit system to have a 99% accuracy rate. (Photo courtesy of Sarasota County Sheriff’s Office.)

One testing cycle that ended Aug. 2, 2007, showed the Printrak 10.1 registering a 99.1 percent accuracy rate for tenprint matches. That meant the system missed 11 of 1,352 submitted prints, according to documents Barati downloaded.

Another testing cycle two months later showed the accuracy rate comparing latent to tenprint searches was 49.33 percent. These reports were never shared with the FDLE, according to Barati, and in October 2008, Motorola shipped the software to the FDLE headquarters in Tallahassee for a “controlled customer introduction,” where Motorola engineers worked to integrate it with FDLE’s existing systems.

In a Nov. 29, 2008, status report, Motorola engineers recorded three incidents that were categorized as a “total system failure,” and 38 incidents that were categorized as “critical failure.” By December, the table that would normally show the accuracy of the latent to tenprint search was simply left blank, which Barati said was because the results were too poor to record.

One of the “total system failure” incidents was when a Motorola engineer recorded a “strong false hit” while testing the system, which meant the system positively identified two prints that did not match.

By April 2009, the system’s tenprint accuracy had declined to 99.0 percent, and the latent print to tenprint accuracy rate was only up to 64 percent. This was also the month Motorola completed the sale of its biometric unit to Sagem Sécurité, a division of the French conglomerate Safran S.A. The unit was renamed MorphoTrak.

It was also the month Barati’s supervisors transferred him off the Printrak 10.1 project. But it wasn’t until 12 days after the company was sold that he was fired. He claimed it was retaliation for his whistleblowing efforts.

Two months later, on June 19, 2009, the contract ended. Motorola had submitted nine payment invoices, at each point asserting that stage of the project was complete.

The FDLE’s Schaeffer stated in his deposition that he and his team “determined that all tests required by the contract … were accurately communicated to me … and if testing resulted in a problem or problems, they were logged, and a solution was either being sought, or the problem was mitigated and resolved.”

But Moyé, Barati’s lawyer, said there appears to be no documentation that Motorola informed FDLE about the problems. When Moyé requested all the relevant test documents and reports from the FDLE, the system failure reports were not included. “Those documents are not there,” Moyé said. “The information was not even there.”

The sale of the company and the end of the contract did not mean the work on the AFIS had come to an end. In October of 2009, the FDLE purchased an extended warranty retroactive to June for about $5 million. Then between Feb. 24, 2010, and Dec. 11, 2012, FDLE officials made seven more requests for money from the state legislature for “maintenance and technical support” for the system, including new software to run its most critical function– “fingerprint matchers.” The total for the extended warranty and all the additional expenditures came to $9.2 million, in addition to the $7.4 million contract price. The contract originally estimated maintenance would be $835,000 a year.

By October 2013, when it requested another $2.1 million for fixes, FDLE officials were openly acknowledging that the system’s performance was poor and slowing down law enforcement investigations. The total was now $11.3 million.

“The FDLE realized it was no longer financially feasible to maintain the system on life support,” Barati said, “so they asked to replace the system.”

The appeals court has not yet ruled on the Attorney General’s motion to dismiss the case. The trial date, meanwhile, is scheduled for March 31.

The nonprofit Florida Center for Investigative Reporting is supported by foundations and individual contributions. For more information, visit fcir.org.