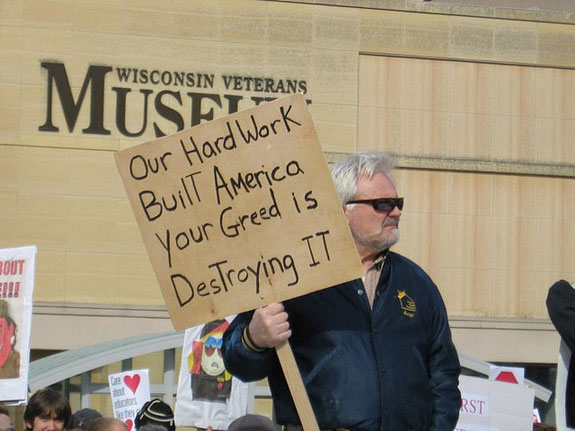

In Wisconsin this year, labor unions protested against proposed budget cuts that would have reduced salaries and benefits for the state’s middle-class workers. (Photo courtesy of UFCW.)

By Donald L. Barlett and James B. Steele

On his last day on the job, Kevin Flanagan, after clearing out a few personal effects and putting them in boxes in the back of his Ford Ranger, left the building where he’d worked for seven years.

He settled into the front seat of his pickup truck on the lower level of the company garage, placed a 12-gauge Remington shotgun to his head, and pulled the trigger. He was 41 years old.

About This ProjectIn The Betrayal of the American Dream, Donald L. Barlett and James B. Steele, in partnership with the Investigative Reporting Workshop, revisit their 1991 Philadelphia Inquirer series, “America: What Went Wrong,” in which they forecast a decline of the middle class. Now they show how the actions of government and Wall Street over the last 40 years have hurt millions of Americans. This is an excerpt from the new book. Related |

He was a computer programmer. He’d been a programmer his entire working life. Until, that is, his job was shipped overseas. The business of moving traditional U.S. jobs abroad — called “outsourcing” — has been one of this country’s few growth industries. It’s the ultimate short-sighted business promoted by the country’s elite because it means lower wages and fatter profits. As for the American workers eliminated along the way, they are just collateral damage.

Kevin was a casualty of the new American economy. Only a few years before, programmers like him were seen as some of the brightest lights of a modern American workforce as technology became the backbone of so many corporate operations.

His employer, Bank of America, did what so many companies now do to their employees. After years of dedicated service, one day they’re told they’re being replaced. Not because they haven’t worked hard enough. Not because they aren’t dedicated to their jobs. Not because they’re not educated or qualified. They’re being replaced because the company, thanks to federal policies, can hire someone else a lot cheaper.

Kevin’s replacement was a programmer from India who had gained admission to the United States under a U.S. government program pushed through Congress by big business. Corporate lobbyists claimed the program was needed to ease a shortage of domestic programmers and computer specialists. In fact, it was a way for corporations to cut salaries.

Kevin was ordered to train his replacement or lose his modest severance package. It ripped him apart. Playing by all the rules had gotten him a pink slip.

Any product or service in America can be imported or outsourced with little or no duty, regardless of where or how it is made. The product may be produced cheaply under dangerous conditions, in a nation with no labor standards or environmental regulations. But to the folks who run the country, that’s OK. Sorry, they say, but American workers will have to pay the price.

The ruling class sold the idea of opening the country to an unrestricted flow of imports on the basis that American society as a whole would benefit: We would buy from other countries, and they would buy from us. But from the start there has never been a balance. No safeguards were ever put in place to prevent other nations from taking advantage of our open-door policy to sell us goods produced under conditions that made their cost artificially low. One of the central manufacturing costs is the price of labor. Inevitably, the consequence of inviting foreign firms into the American market is that labor costs fall to the level of the lowest suppliers.

America essentially invented outsourcing, but few outside the corporate world realized how rapidly it, along with other trade policies, would devastate employment across the middle class as imports quickly overwhelmed exports and workers in industry after industry were sacrificed on the altar of unrestricted free trade.

For the ruling class, this was just fine. Everything was proceeding along the lines of their free market theories. They wanted no restrictions on trade policy, and Congress obliged. They wanted complete freedom to close plants in the United States, set up plants offshore, and outsource work to anywhere in the world without any tax penalty, and Congress obliged. They wanted to stonewall the wage demands of workers back home by hinting that their jobs might be ticketed for the next offshore shuttle if they asked for too much, and Congress went along. With this kind of oversight, was any job safe?

Kevin Flanagan certainly thought his field was safe when he entered it in the 1980s. Computer programming looked like one of the surefire careers for the future. Everyone said so. The advent of large mainframe computers in the 1960s had kicked off the first big increase in jobs, and the demand for programmers rose even more in the late 1970s with the introduction of personal computers and the extension of data processing into more and more businesses. Everyone thought that even bigger growth in programming jobs lay ahead.

It didn’t.

By 2002, the number of computer programmers in the United States had slipped to 499,000. That was down 12 percent from 1990 — not up. Nonetheless, the Labor Department was still optimistic that the field would create jobs.

Wrong again. By 2006, when the number of jobs fell to 435,000 — 130,000 fewer than in 1990 — the Labor Department finally acknowledged that jobs in computer programming were “expected to decline slowly.” It was a telling confession of a huge miscalculation: computer programming and the kind of work it represented — skilled work that usually required a bachelor’s or higher degree — had been assumed to be beyond the capabilities of competitors from abroad with their less vaunted educational systems and lack of English language skills. They couldn’t take that away from Americans, could they? But they did.

Domestic programmers, like millions of workers in other fields, are casualties of a Congress long indifferent to the plight of American workers. Rather than create a level economic playing field, lawmakers and presidents, both Democrat and Republican, have permitted foreign governments to set American job policies by eroding this country’s basic industries. While free-traders in the United States have been busy honking their horns against any form of government intervention in the market, they have turned a blind eye to what has been going on in the globalized world they are so proud of having created. Many foreign governments ignore such theories and subsidize industries that they believe will help their people. In the 1980s, the government of India began supporting its nascent software industry in order to encourage companies to produce software for export. India’s software exports totaled a mere $10 million in 1985; by 2010 they had reached an estimated $55 billion.

Service jobs in fields such as programming once were thought of as a key to America’s future.

As factory jobs were decimated by the imports encouraged by federal policies, service jobs were to take their place. America was in transition, we were told — the brawny factories with their bellowing forges and thunderous stamping machines were simply giving way to entirely new workplaces with sleek workstations housed in office towers.

The future might seem bleak to anyone who worked in a factory that made cars or shoes, but the nation as a whole would adjust and move on to greater things. America always adapts, we were told. Isn’t that what makes America great?

But there were fatal flaws in this theory. The first was that America’s corporate leaders saw quickly that they could make enormous profits producing goods offshore rather than reinvesting at home. Labor was cheap abroad, and the developing countries would do anything to get the jobs. And none of these other countries were subject to the regulations that U.S. companies had to adhere to: fair labor standards, workplace safety rules, environmental standards — all rules that most Americans supported to make the nation a more livable place. As a bonus, thanks to corporate lobbying, whatever these U.S. companies made abroad under primitive conditions using slave labor they could bring back to the United States paying little or no import tax.

The other flaw in the theory, and the one that will be causing grief for working Americans for years to come, is that while China and India may be poor countries, each has millions of very bright, talented people eager to work at a fraction of what bright, talented people need in the United States to maintain a middle-class lifestyle here.

The first of the service jobs to be outsourced in great numbers were the back-office operations of banks, investment houses, insurance companies, and any business that processed huge amounts of paper, from credit card charges to procurement manifests to legal exhibits. Most of this work went to India, and as the industry grew, American corporations began sending more work there.

The earlier phase of outsourcing was known as business-process outsourcing (BPO). The latest is called knowledge-process outsourcing (KPO). The corporate focus has expanded to the highly sophisticated operations that represent, in the words of one management consultant, the “very heart of the business … involving complex analytics.” Where an earlier generation in India might have been reconciling credit-card balances, today they perform statistical analyses, run growth projections, and do all the other things that number crunchers back home do — or once did.

The global consulting firm KPMG explained the appeal of KPO in a 2008 report: “Knowledge-process outsourcing (KPO) enables clients to unlock their top line growth by outsourcing their core work to locations that have a highly skilled and relatively cheap talent pool.”

This phrase should send a shudder down any economist’s spine because it says out loud, albeit with a bit of jargon, the truth that cannot be spoken if you believe in a growing economy and shared prosperity: Companies can get richer by moving the essence of what they do to cheaper countries. Why be located in the United States at all?

An ever-greater share of sophisticated analytics as well as creative jobs that were once done by middle-class Americans are being shipped offshore. Indian vendors create advertising copy, high-end photography, marketing brochures, graphic art, original illustration, and even music videos for the U.S. market-all at a fraction of what that work would cost in the States.

Outsourcing is beloved by management consultants, and none more so than Accenture. The world’s largest consulting firm, Accenture is a $25 billion a year global enterprise and a far cry from its days as a modest unit within the Arthur Andersen accounting empire in the United States.

Since branching out on its own, Accenture has reaped untold riches helping U.S. companies send work out of the country. Every year Accenture is voted the “top outsourcing service provider globally” by professionals in the industry, a distinction that a spokesman says the company earns by taking “outsourcing deeper” than others.

Deep into its own ranks, it turns out. Petitions are on file with the Labor Department by onetime Accenture employees in Atlanta, Ga.; Birmingham, Ala.; Chicago, Ill.; Dayton, Ohio; Morristown, N.J.; Richfield, Minn.; Wilmington, Del.; and other cities. Their jobs as software developers, global management consultants, accountants, and financial agents were eliminated by Accenture in the United States and shipped to Argentina, Brazil, India, the Philippines, and other countries.

Whatever you say about Accenture, the company practices what it preaches.

One of the most overlooked — and most frightening — forecasts about the future of the middle class was released in December 2008. This was a study by researchers at the Labor Department that identified service jobs that might go offshore. Despite its scholarly tone, its conclusions are alarming.

It found that as many as 160 service occupations — one quarter of the total service workforce, or 30 million jobs — could go offshore. Jobs in those 160 categories were growing at a faster rate than service jobs overall and, ominously for future middle-class incomes, they were among the higher-paying service jobs. The Bureau of Labor Statistics calculated the annual wage for these jobs at $61,473 — significantly higher than the $41,610 in annual wages for all service occupations.

The most revelatory aspect of the BLS report was how surprised by its conclusions its authors seemed to be. The agency that specializes in economic matters affecting working Americans has spent little time looking at what may be an Armageddon for service workers. But that’s in keeping with the perennial optimism that economists generally peddle about the direction of the American economy when the subject involves free trade. Why give much ink, these optimists reason, to a problem that doesn’t fit the prevailing theory that offshoring is good?

One of the few economists who did sound an alarm on off-shoring, Alan S. Blinder of Princeton, was roundly criticized by his fellow economists when he predicted in 2007 that the off-shoring of service jobs from rich countries to poor countries “”may pose major problems for tens of millions of American workers over the coming decades.”

While it’s clear that free trade, as practiced by the United States, is driving down the income of millions of working Americans, the economically elite are sticking to their message that America is on the right track.

Harvard economist N. Gregory Mankiw, a former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, says that the migration of jobs from offshoring makes economic sense and is “the latest manifestation of the gains from trade that economists have talked about at least since the days of Adam Smith. … More things are tradable than were tradable in the past, and that’s a good thing.” For decades, Americans have been given misleading assurances like that.

Gary Clyde Hufbauer, a former deputy assistant secretary at the Treasury Department, predicted in a research paper that was widely picked up by the media that NAFTA would “generate a $7 to $9 billion [TRADE] surplus that would ensure the net creation of 170,000 jobs in the U.S. economy the first year.” Instead, NAFTA caused an immediate trade deficit with Mexico. By 2012, the cumulative total was $700 billion. More importantly, NAFTA wiped out hundreds of thousands of good-paying manufacturing jobs in the United States.

Hufbauer is still in the job-predicting business at a Washington think tank. One of his latest:

“When American multinationals go overseas, on balance, they create more jobs here in the United States than they would have if they’d not gone overseas.”

Right.