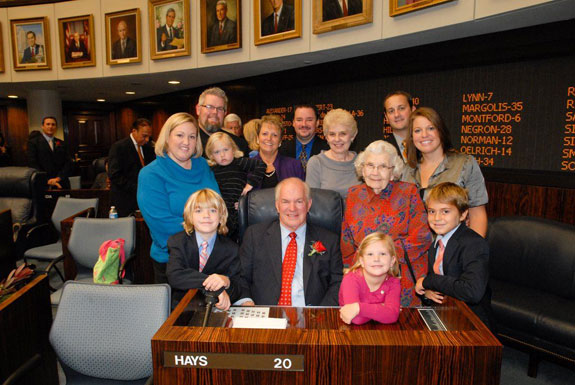

Sen. Alan Hays, pictured here with friends and family in the state Senate, said there are "many Hispanic-speaking people" that shouldn’t be counted during the redistricting process. (Photo courtesy of Florida Senate.)

By Ralph De La Cruz

Florida Center for Investigative Reporting

“Since time immemorial, the drawing of lines has been done to benefit those in power,” the NAACP’s Leon Russell said at a redistricting forum in Miami earlier this month.

In the United States, the drawing of lines is called redistricting. Using Census figures, redistricting happens every 10 years. The way the lines are drawn affects every political office from school board to Congress. And because the process is run by the very people — state politicians, no less — who are affected by it, it’s been notorious for manipulation.

How is redistricting manipulated, and why should you care?

A sharp person with an up-to-date Census map could probably draw a district that would make liberal Armenian dentists a majority — which would then be more prone to elect a liberal Armenian dentist. That’s fine, unless most of the people in the area are actually conservative Jamaican painters who end up feeling unrepresented and disempowered.

Florida has proven particularly fertile for manipulation. In 1972, the federal government determined that when it came to drawing political boundaries, Florida was not in compliance with the 1965 Voting Rights Act. And that, from then on, the feds would monitor and have to clear any changes to voting and election laws in five Florida counties — Hendry, Collier, Hardee, Hillsborough and Monroe (Gov. Rick Scott and Secretary of State Kurt Browning filed a petition just two weeks ago asking federal courts to do away with that provision of the law.)

Favorable line-drawing during redistricting has helped the Republican Party maintain super-majority control of both chambers of the statehouse despite the fact that a majority of registered voters statewide are Democrats.

All of which led Florida voters to pass Amendments 5 and 6 — the Fair Districts Amendments — last year, which forbid the drawing of districts to favor a party or individual, or to diminish the impact of racial and ethnic minorities.

Redistricting is complicated business made more so in Florida by the passage of the redistricting amendments and the expanding Hispanic population. That population increase is a major reason why Florida is expected to add two Congressional seats this year.

With such a complex and potentially contentious process, the last things you need are political hyperbole and racial controversy.

“Before we design a district anywhere in the state of Florida for Hispanic voters, we need to ascertain that they are citizens of the United States,” state Sen. Alan Hays said Tuesday. “We all know there are many Hispanic-speaking people in Florida that are not legal. And I just don’t think it’s right that we try to draw a district that encompasses people that really have no business voting anyhow.”

Bad enough that a state senator enters the redistricting process with an assumption that there are “many Hispanic-speaking people” that shouldn’t be counted. Worse that he’s on the Senate Reapportionment Committee, one the folks who’s actually putting together redistricting maps. And even worse that Hays doesn’t know the majority Hispanic group in the Central Florida area he was referencing are Puerto Ricans, who are, by definition, American citizens.

But perhaps Hays’ worst offense is that he, a lawmaker, doesn’t know the law.

As Juan Cartagena of the Puerto Rican political group LatinoJustice pointed out in an opinion piece, the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution requires representation of all people, not just registered voters.

If Hays is worried about “people that really have no business voting anyhow,” he’d have to make sure that anyone under 18 wasn’t included. And if it’s about legal status, where exactly is the cutoff for Hays’ you-don’t-count line? Do resident aliens count? What about citizens who aren’t registered?

It didn’t take long for Hays’ remarks to draw a sharp response from Hispanic lawmakers. Democratic Rep. Luis Garcia called for a public apology and Rep. Janet Cruz demanded he be removed from the reapportionment committee.

Sen. Rene Garcia, the head of the Hispanic Caucus gave Hays a pass by saying he was “comfortable” given Hays’ response that he’d be willing to talk to any legislator who had an issue with what he said. But it was obvious not all Hispanic Republicans were as comfortable with Hays’ words.

“I think that it is unfortunate that anyone would question whether or not Hispanic voters are American citizens,” said Rep. Jose Diaz, a Miami Republican. “It is basic Government 101 that in our country only U.S. citizens can exercise the right to vote.”

And that everyone counts.